The most recognizable work at the Whitney Museum's new modernism exhibit may be a tarot deck

发布时间:2022-11-08 23:48:30 人气: 作者:Heather Greene

(RNS) — A little-known 20th-century artist and occultist, Pamela Colman Smith, is featured in a new exhibit at New York City’s Whitney Museum. While most of Smith’s work, like her name, has been lost to history, there is one project that has remained popular. Today, that single project may arguably be the most recognizable work in the museum’s exhibit: the Rider-Waite-Smith, or RWS, tarot deck.

“Smith was a quintessential early 20th-century American modernist in her desire for an art that bypassed reason and materialism in favor of expressing her unconscious and inner feelings,” explained Barbara Haskell, curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

“Smith’s symbolism was the initial expression of the desire among American artists to express the spiritual in art,” Haskell said.

The Whitney exhibit, “At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism,” celebrates “the myriad ways American artists used nonrepresentational styles” to express a response to their changing environment, political movements and other facets of the modern age, according to the museum’s website. The exhibit includes well-known artists, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, as well as more obscure names like Smith’s.

On display are two of Smith’s works: “The Wave” (c. 1903) and a full tarot deck, originally printed between 1920 and 1930. While Smith is best known — or only known — for the deck, these two pieces are a fragment of her life’s work.

“The Wave” by Pamela Colman Smith, 1903. Image courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art

Born in London in 1878 to American parents, Smith was raised in the U.K. and Jamaica and spent time in New York City, where her family originated. She studied art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and was considered a child prodigy, according to biographer Stuart Kaplan in his book “Pamela Colman Smith: The Untold Story.”

During her life, Smith was prolific. Beginning in the 1890s, she illustrated more than 20 books and even more magazine articles, according to Kaplan. She authored her own set of Jamaican folk tales, co-edited and illustrated A Broad Sheet with Jack Yeats, and launched her own literary magazine, The Green Sheaf. She also created popular miniature theater performances and often publicly performed her folk tales and poetry.

Despite the breadth of her work, Smith’s public legacy rests squarely with a project she dismissed as “a big job for very little cash,” according to Kaplan.

In 1909, Smith was offered the job by occultist and mystic A.E. Waite, who met her through their shared membership in the Isis-Urania Temple of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. During this period, spiritualism and other occult practices were at the height of popularity in the U.S. and the U.K.

Pamela Colman Smith in 1912. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia/Creative Commons

Smith was not only an acknowledged psychic but also had synesthesia; she could see music, which comes through in her art. “For many American artists — as it was for Smith, who made the work in the exhibition while listening to Bach — music was seen as a vehicle for liberating the unconscious,” explained Haskell.

Although Waite did recognize that Smith was an “imaginative and abnormally psychic artist,” writes Kaplan, Waite did not believe she possessed a deep enough understanding of occult symbolism and would need his help. However, it’s unclear how much direction he ended up giving her.

Smith finished all 78 images in just a few months, and the deck was first published in late 1909 by The Rider Co.

Smith’s imagery is eclectic in representation, pulling from a number of religious and spiritual systems. This reflects both Waite’s and Smith’s personal interest in Judeo-Christian mysticism as well as Smith’s personal fascination with folklore and myth.

Biblical symbolism, for example, is found in the Lovers card (VI), the Judgement card (XX) or the Devil (XV). Jewish mysticism is represented in the Wheel of Fortune card (X) or the High Priestess (II). Similar images are peppered throughout the deck, living comfortably alongside pentacles, wands, magicians and other occult symbols.

Waite was wrong, believes Jaymi Elford, a professional tarot reader and author of “Tarot Inspired Life.”

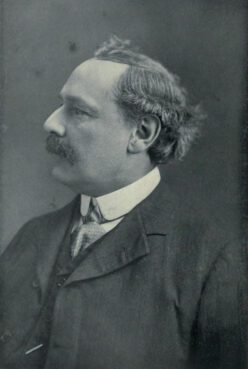

A.E. Waite in 1911. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia/Creative Commons

“Smith did understand the symbolism,” she said, which enabled her to “breathe life into (the deck) and give it movement.” Elford believes Waite’s comments were probably more a function of typical misogyny than a true assessment of Smith’s esoteric knowledge.

Smith’s theater and storytelling background are very evident in the images, Elford said, which makes the cards more accessible, allowing anyone to tap into their deeper meanings despite the lack of ethnic and racial diversity in the representation of its figures.

When Elford offers public readings at events, she allows her client to select a deck for the reading. The RWS, she said, is the deck most universally asked for. This may be because of the deck’s ubiquity even outside the occult world. It has been featured for decades in television shows, including AMC’s “Mad Men” (2007-2015) or Netflix’s “The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina” (2018-2020), and in movies such as “Nightmare Alley” (1947) and “Live and Let Die” (1973).

The deck’s popularity was boosted further in 1971, another period that saw a tarot renaissance, when U.S. Games purchased the rights to publish and distribute the deck worldwide. As a result, it became more widely available to the public. Since that point, U.S. Games has never taken the deck out of publication and, along with other publishers, has created many adaptations.

However, that alone still doesn’t account for its longevity and its popularity among readers. Teachers often insist students begin reading with an RWS deck, chiefly because it has become the standard-bearer for the development of new decks.

“Everything we know, all these current decks that we’ve got out here, trace their lineage down to the RWS deck,” said Elford, who tells students to get both a deck they love and an RWS deck. “There is something about that deck,” she added.

Installation view of “At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism” at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. The Rider-Waite-Smith tarot deck by Pamela Colman Smith is in the foreground. Photograph by Ron Amstutz/Whitney Museum of American Art

Much about Smith’s personal life has been lost to history — as often happens to women artists, occultists and storytellers. In 1911, she left the occult world behind and converted to Catholicism, remaining devout until her death in 1951.

Although she continued producing works until the end of her life, it is the tarot deck that heralds her legacy today and has brought her renewed recognition.

The Whitney Museum is joining the effort to lift up Smith’s name and rediscover the whole of her art and its cultural importance. The exhibit, as Haskell says, seeks to “reveal the Symbolist roots of American modernism.”

The famous deck once called Rider-Waite, after the publisher and writer, is now being called Rider-Waite-Smith or simply Smith-Waite.

Including the tarot cards in the museum’s exhibit, Haskell said, demonstrates that “the desire for an alternative to reason and materialism was not limited to the elite art world but instead was widespread.”

It is Smith’s art style that made that possible, capturing the complexities of mysticism and occult symbolism and making them accessible, as Elford says, “through a unique storybook quality.”